The “Interurban” system of electric railways in Ohio, Michigan, Illinois and Indiana was arguably the finest large area transportation system in the world in the early part of the twentieth century. Steam railway passenger service provided more comforts and faster travel between major cities but the Interurban Cars served thousands of small towns and villages that had no other public transportation available.

The Interurban system linked virtually every city and many towns and hamlets in the 4 states with a fast and efficient means of getting people and goods from one place to another. It’s a crying shame the leaders of the day didn’t have enough foresight to keep it operating. Even if it had to be done with public money.

The Electric Light Rail and Trolley systems were made possible by the work of Werner von Siemens in Germany and Frank J. Sprague, Sidney Howe Short, Charles J. van Depoele, J.C. Henry and a few others in the US. Sprague, a graduate of the Naval Academy, was a brilliant engineer who developed the first practical “non sparking” DC electric motor suitable for driving a light railway car. He also developed a means of transferring electrical power from an overhead line to a moving railcar.

At the beginning of 1888, there were 13 electric railways in the U.S., with 95 motor cars and 48 miles of track. Just a year later, in 1889, there were 805 miles and 2800 cars; in 1899, 17,685 miles and 58,569 cars; and by 1909, there were some 40,000 miles of electric railway. This was an amazingly rapid technological advance. In less than a decade after the first experiments in 1880, the technology was approaching maturity, and the standard practice was established.

How They worked

The most practical motors of the day for driving electric railway cars were 600 Volt DC motors. Direct Current (DC) has the inherent problem of significant “line loss” when tranmitting low voltage power over the long distances of a statewide system. This meant the early Interurban systems would have probably transmitted high voltage, 3 phase alternating current (AC) to power substations where the AC would have been converted to 600 Volt DC for use by the Interurban Cars. This scheme would require a substation about every 10 miles along the right of way.

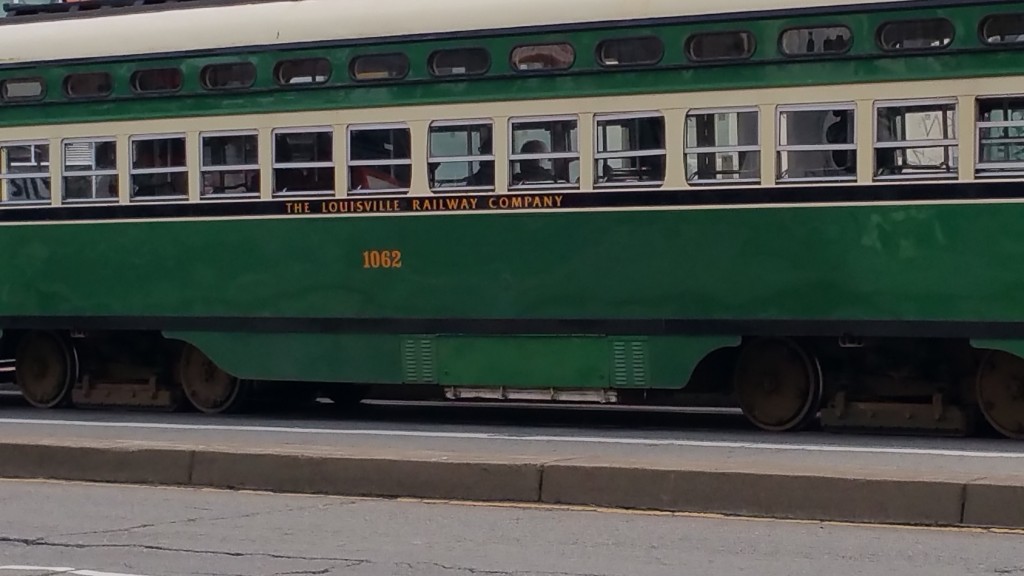

The Cars

Some leading manufacturers of interurban cars were J. G. Brill of Philadelphia, American Car Company and St. Louis Car Company of St. Louis, Cincinnati Car Company, and Jewett Car Company. Electrical equipment was by Westinghouse, General Electric and Reliant, among others.

The individually powered, passenger-carrying car greatly predominated on interurbans. Most common were two-truck cars with two or four motors, resembling steam railway passenger cars. Smaller four-wheeled cars, called “single-truck” though they had no truck at all, but axles fixed in the car frame, were used for lighter duties and streetcar routes. Nonpowered cars of each type, called “trailers,” were sometimes used behind power cars, but many companies used no passenger trailers at all. Cars ranged in length from 16 ft for a single truck, to 45 ft and even longer, with 32 ft or 40 ft being common. Electric railway cars were normally a little over 8 feet wide. A typical car would seat 48 or 50 passengers, and carry twice as many with standees. Early cars were all-wood, like the horse cars, with hand brakes and quite light. Steel underframes were introduced early on. After 1916, steel underframes were required for interstate service, but by that time most cars had steel underframes anyway. Later, all-steel cars became standard, as on steam railways.

Smaller cars consisted of one compartment with a motorman’s station at each end. The seating could be longitudinal cane benches as familiar from streetcars, but cushioned steam-railway coach seats were more usual for the longer interurban journeys. Passengers entered by steps at each end. Larger cars might have a separate motorman’s compartment, often combined with a parcels and baggage area with a wider door, a smoking compartment, and a general or ladies’ compartment. Entry could be by a center door, with smoking compartment to one side and the ladies’ compartment to the other, especially on the longer cars. A single-ended car had a controller at one end only, while a double-ended car had controllers at each end, so that it could be driven from either end. To reverse the car, all that was necessary was to raise the proper trolley pole (if the car had two) or to rotate a single pole by 180°, and carry the control and brake handles from one end of the car to the other. A single-ended car had to be turned on a loop or wye track at the terminus. (turntables were rare on interurbans).

Early cars were heated by stoves, then many had steam heating from coal-fed boilers in the cars. Later cars generally used the safer and less bothersome electric heating. The disadvantage of electric heating was that it went off when the power went off, making a stranded car in cold weather rather uncomfortable. Of course, the cars had electric lights, including an electric headlight. A location above the front window was most effective for a headlight, but they were usually below the front window so they were easy to reach to change the bulb. Cars often did not have those comforts of a steam train, the toilet and the water cooler. Later heavy interurbans included these features, of course. The motorman could attract attention by a foot-operated gong or bell. After air brakes were fitted, an air whistle was possible. The gong was used while running in streets, the whistle out on the line. These whistles were shrill and high-pitched, which, after all, was most effective. Inside the cars, advertising cards in a row above the windows were a common feature.

This is a picture of the crew laying the Interurban Tracks

through downtown Knightstown in 1901.

(source: http://www.chicagorailfan.com/indt1923.html)

(source: http://www.chicagorailfan.com/indt1923.html)

interurbans were quite fast . lehigh valley transit ran lines from phils

pa to easton pa until 1949 and 1951 . phila cars ran 75 t0 80 mph rangeda

Hello,

Is there a map that displays the interurban routes from other cities, leading into downtown Indianapolis toward the tracking station? Basically, how would I find the Alexandria-Anderson interurban’s path? Where did it enter the city and what path did it take to the downtown tracking station?

Thank you!