This building is always a blast from the past, last time I visited this place, was 17 years ago! It is a strong piece of architecture. A residence located across the street from University of Chicago (U of C, not UIC, just so you don’t say the wrong acronymn). It sits on a corner lot, long and horizontal, layered and tall, it’s quite impressive for a house built in the early 1900’s.

I know it was one of the first houses to used steel beams to reinforced cantilevers, to accentuate the horizontal. The long roman bricks, the deep eaves, ribbons of art glass all add to the horizontality of the project. The steel beams where quite the technology for the time, very sophisticated. Also note that light bulbs were often not covered to show off the “new” technology.

Text from the book “The Decorative Designs of Frank Lloyd Wright” by David A Hanks, 1979 E.P. Dutton, New York, p105-110 on the Robie House.

“….the Frederick Robie House (fig. 106) on Woodlawn Avenue in Hyde Park (1908) is contained within a city lot, and the more sober materials of brick and concrete replace the ephemeral plaster and tile walls of Coonley House. The tightness of the Robie plan makes it seem more like a ship than a house. Its huge chimney acts as a mast, balancing and weighting down the rest of the house, which would otherwise seem suspended. The plan of the second floor is open and fluid, with the living room and dining room as one area separated by the fireplace and the central stairs. Each of these rooms has a triangular-shaped bay, and these bays appear as bows of a ship. The family bedrooms are in a smaller area on the third floor. The ground floor reflects the first, with the billiard room and playroom beneath the living and dining rooms. Each major room has access to the porches and balconies, which are lined with flower boxes.

Fireplace here, featuring a “room within a room”

Although not nearly as large as the Coonley House, the Robie House also had a complete decorative scheme for the interior, which was supervised, as already noted on pages 44-45, by the Niedecken-Walbridge firm in Milwaukee. Again, George Niedecken, under Wright’s direction, was responsible for supervising the execution of the interior, including developing the designs for furniture from concept sketches to presentation drawings.

Interior of Robie House Living room.

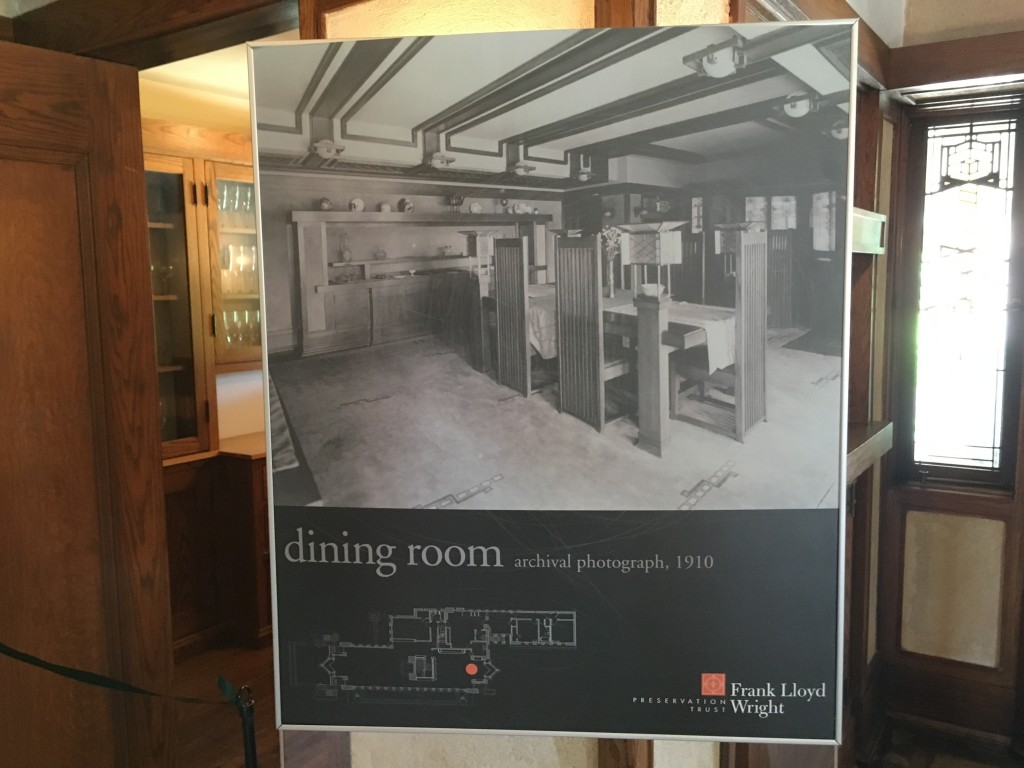

Fortunately much of the Robie furniture has survived and is now owned by the University of Chicago, which uses the house for its development office. Extensive remodeling of the interior from 1967 to 1968 made use of a few pieces of the furniture, while most, including the dining room ensemble, is kept at The David and Alfred Smart Gallery. Although the dining room was altered drastically, with the removal of the dining room table and chairs as well as the built-in buffet, it still retains its trim, which defines the space, and its original light fixtures, which can be regulated by a dimmer. The custom-designed hand-woven rugs were removed from the house long ago, though the working drawings and even the yarn color samples are in the Niedecken collection at the Milwaukee Art Center. Most of the windows still remain in the house, and the example in figure 110 is typical (art glass). Its design is based on two conventionalized flowers on both sides of an angular composition that reflect the floor plan of the house.

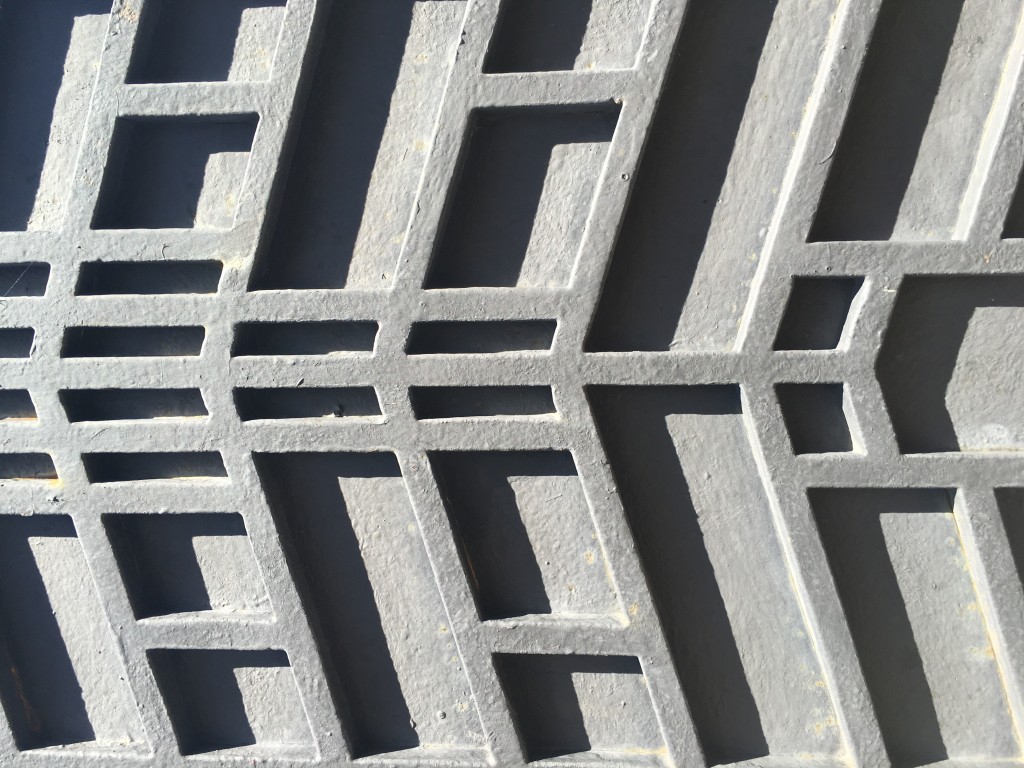

Art Glass from exterior at Robie House

The Robie dining room table and six chairs (fig. 107) formed Wright’s most important furniture ensemble. Whereas Wright was uneasy about the disarray that a living room seemed to require, a dining room was for him “always a great artistic opportunity.” The occasions of “dining” and of “living” were different. Norris Kelly Smith has pointed out the symbolic significance of this ensemble, where a family “at dining” could participate in a great oneness of purpose:

Photograph of original FLW Robie house furniture, dining table with tall back chairs. Notice the smaller table behind. The architect was concerned with making “rooms within rooms” to break down large spaces.

“In his early houses Wright consistently treats the occasion almost as if it were liturgical in nature. His severely rectilinear furniture, set squarely within a rectilinear context, makes these dining rooms seem more like stately council chambers than like gathering places for the kind of intimate family life we usually associate with Wright’s name. They declare unequivocally that the unity of the group requires submission and conformity on the part of its members. (Frank Lloyd Wright: A Study in Architectural Content, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1966, p. 74)

Beginning of mitered glass corner, Art Glass at the Robie house.

This type of formal family dining requiring conformity must not have appealed to the Robies, since according to their daughter Lorraine Robie O’Connor, her parents preferred to dine at the smaller table in the “prow” of the dining room, and the formal table was reserved for guests. The formal dining was Wright’s idea about his family at dining, not necessarily the clients’.

Photo of original living room at Robie House.

The Robie dining ensemble is an impressive and moving aesthetic experience, especially when seen in the context of the original setting, where it achieves even greater power. The visual relationships between the dining furniture, conceived in its vertical and horizontal lines, and the interior architecture contributed to the overall unity of the room. The strong horizontal thrust of the extended top of the dining table and of the built-in buffet had their exterior counterpart in the cantilevered roofs. The vertical lines of the high-backed chairs were echoed in the buffet.

Entry into the second story Robie House

According to the account book kept by H. Barnard, contractor for the Robie House, cash disbursements were recorded from April 15, 1909, through June 21, 1910. The documentation for the completion of the Robie interiors is in the journal kept by George Niedecken between August 4, 1909, and December 31, 1910 (Prairie School Archives, Milwaukee Art Center). Clearly Niedecken, as interior decorator, supervised the execution of the Robie dining room. His account book indicates that the furniture was made by the F. H. Bresler Co. of Milwaukee and that leather for the chairs was purchased from the Federal Leather Co. (Niedecken’s role in the design of this furniture has been discussed on pp. 43-44).

Replica of original FLW designed couch, original now on display at MET in NYC.

The dining table originally could be extended, which explains the extra set of legs. The piers and end sections could be moved and extra leaves inserted for larger dinner parties. The table was drastically altered some time after the Robies left in 1911. The four piers and lamps were removed, probably in order to shorten the table or because they were in the way; these presumably were destroyed. In 1972 they were reconstructed from drawings photogrammetrically plotted from original photographs of the dining room for the traveling exhibition “The Arts and Crafts Movement in America 1876-1916” (an exhibition organized by The Art Museum, Princeton University, and The Art Institute of Chicago; catalogue edited by Robert Judson Clark, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1972). Recently this preliminary restoration has been refined. The Robie dining room furniture represents a culmination of Wright’s efforts in designing integral furnishings, the beginnings of which had been seen in earlier houses.

Continuous window wall was a common feature of FLW’s work, as the building would open to the landscape.

The watercolor rendering of the rug plan (fig. 108) gives the floor plan of the first floor, with varying patterns indicated for different rooms. Although shown here as wall-to-wall carpeting, area rugs were actually executed, as seen in figure 107.

Carpet with Motif, Robie house Living room, 2nd floor, photo by author, July 2016

A thorough documentation of the execution of the Robie House is possible through the Niedecken journal and the Barnard account book. The latter includes an entry that indicates that the South Halsted Iron Works had the contract for the metalwork, which probably included the gates seen in figure 109. Frederick Robie, Jr., also is seen here in his toy automobile. The design for the now-demolished gate reflects the windows almost exactly.

Detail of Iron work in Gate at Robie House, Photo by Author

In the fall of 1909, after twenty-two years of successful architectural practice, Frank Lloyd Wright, feeling that he had reached a creative plateau, left family and practice to go to Europe. After a sojourn in Berlin, Wright moved to a small villa at Fiesole near Florence, Italy. There he worked on preparing a retrospective publication of his work. This departure marked the close of Wright’s first remarkable and productive period of work. ” Wright left America to work on this Wasmuth Portfolio.

Recent Comments